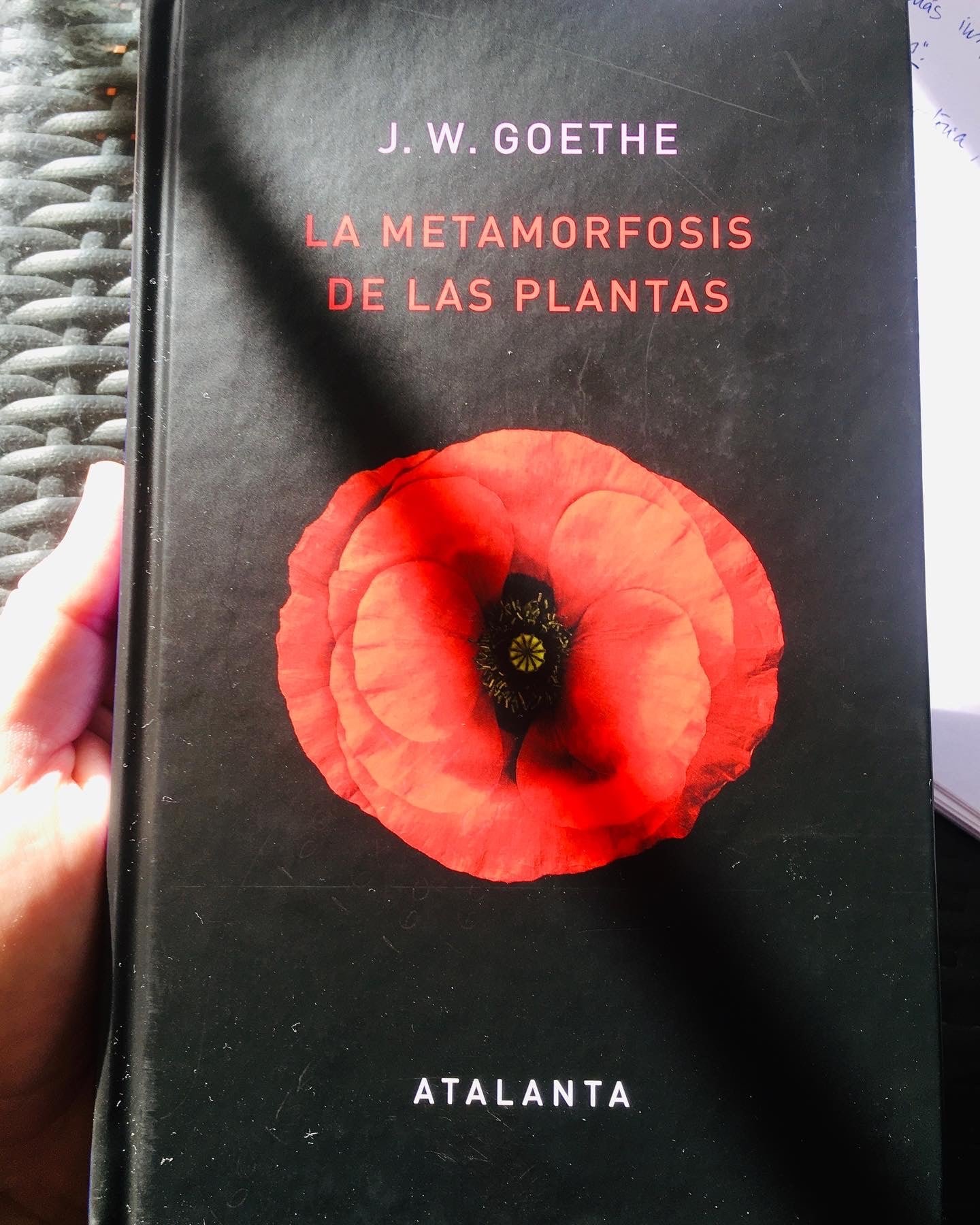

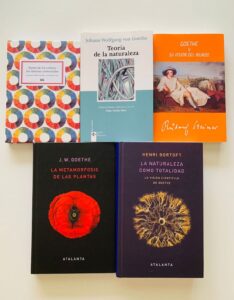

In 2022, the publishing house Atalanta published in Spain the beautiful and delicate work of Professor Gordon I. Miller, of Seattle University, who has republished The Metamorphosis of Plants, a work by the German philosopher and writer Goethe (with wonderful illustrations and photographs, by the way).

In this post I would like to share with you some excerpts, mainly from the introduction and the epilogue, about what I found most interesting and applicable to our work in the vineyard: the way we observe the plant world, which is one of the basic pillars of biodynamic agriculture and of Rudolph Steiner's general vision.

Steiner translated much of Goethe's scientific work and was his main inspiration throughout his life. These were the beginnings of modern science and perhaps the moment when the paths forked, on the one hand the mechanistic materialistic science of Newton's hand, and on the other hand those who tried not to separate science from poetry, matter from spirit. The science that triumphed was mechanistic science, and it has allowed us to make great advances in society. However, these advances have in many cases been costly at the environmental and human level.

In our now, and thanks to that science, we may be in a position where we can attend to other sensitivities that link us to nature, rather than fight against it.

GOETHE AND STEINER

Steiner's reference was Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Goethe glimpsed the existence of a deeper dimension in the life of plants, beyond what can be empirically seen, touched, smelled or classified, which consolidates and guides the formation and transformation of plants.

For him poetry and science had to go hand in hand, just as “spirit and matter, soul and body, thought and extension (...) are the basic pairs of ingredients of the universe and will remain so forever”.”; and wondered why “people have forgotten that science has developed through poetry and were wrong not to contemplate that a swing of the pendulum could bring them together and take them down to a higher level to their mutual benefit”.

He asked the prevailing currents of science: “Can a mechanistic, materialistic approach, focusing on innumerable individual surface structures, meet the challenge of explaining the living organism or the life of nature as a whole?.

Goethe proposed a union, not a division; a connection with a “delicate empiricism that is formed identically with the object”.

This holistic and integrative vision was inspired by Baruch Spinoza, who argued that spirit and matter are the basic ingredient pairs of the universe and will always remain so. And that is why, the observer must employ “both the eyes of the body and the eyes of the mind, both sensory and intuitive perception, in constant and spiritual harmony”.”. This form of knowledge was ultimately based on a harmony and identity between the human spirit and the informing spirit of nature, in which “one spirit speaks to the other”. And for this, Goethe proposed a method of understanding, which he called the genetic method, - not in relation to genes, but in relation to the genes of plants. In line with Spinoza, he postulated that nature could be conceived in two ways: as creative power and as created power. The same approach was already put forward by Spinoza, who differentiated between natura naturas (creative nature) and natura naturata (created nature).

And he worked to complete empiricism with imagination in order to see nature completed and unified as creator and creation.

The first part of the method consisted of observing the formative stages of the plant or an element of it, such as the leaf, seeing the differences of each step. The second part of the method required what Goethe called “exact sensory imagination”, which consisted of imagining common laws of such a formative process. But Goethe went a little further. In this imagining he defended a “knowledge from within”, breaking the duality of a “curious subject who knows a strange object” and proposing a knowledge thanks to the participation or even the identification of observer and observed.. As he said “our spirit enters into harmony with those simpler powers which lie beneath nature and is able to represent it as purely as the objects of the visible world are formed to a clear eye”.

Goethe called the two cognitive faculties involved in this endeavour: “understanding” to rational thought (which is the common instrument of conventional science) and “reason” to the intuitive perception that nourishes the poetic sensibility. That sensibility, “when it aspires to touch the divine, must deal only with what has become and is alive; the (rational) understanding, on the other hand, deals with what has already become and fossilised, in order to be able to profit from it”.

“Through an intuitive perception of the eternal creative nature, we can become worthy of participating spiritually in its creative processes”. Somehow “Goethe was aware that perceiving the essence of metamorphosis implied a beneficial metamorphosis in the essence of the perceiver” concludes Professor Miller in his fantastic book.

A further step was taken by Steiner, who not only observed and understood, but also found ways to intervene in plants through his biodynamic agriculture.